If you happen to be wondering what a prostate biopsy is like, this article should prove helpful.

In August, I underwent something called a transperineal prostate biopsy and I thought sharing my experience might be helpful to other people who are facing this procedure.Like most prostate biopsies, mine was performed to evaluate whether or not the patient has prostate cancer. That means biopsies can be an emotionally challenging experience as well as a physically daunting prospect: a scary procedure at a scary time.

|

| NCI's Dictionary of Cancer Terms |

However, while I find the thought of needles piercing sensitive parts of my body unappealing, I found that this procedure can be relatively quick and painless. I say that based on my experience and the feedback of several other guys whom I chatted with over tea and biscuits in the recovery room. This should be positive news, given that a biopsy is an essential weapon in the fight to find and treat prostate cancer.

What is a transperineal prostate biopsy?

To be specific, the procedure I had was a transperineal prostate biopsy, and even more specifically, an LATP or Local Anesthetic Transperineal Prostate Biopsy. This terminology is explained—from a doctor's perspective—and graphically visualized in the video below. Note that the video contains some drawings of male genitalia:While that video is very informative, I thought it would still be helpful to write about my LATP from a patient's perspective (bear in mind that I am not a doctor and this article is not medical advice). Of course, the web has lots of professional articles and videos about the technical aspects of this procedure, so I have put links to some of them at the end of the article.

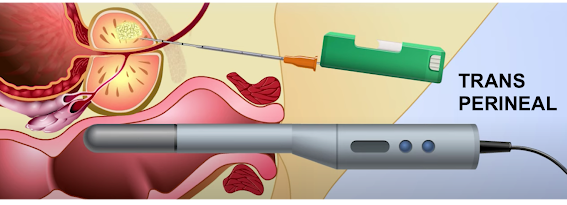

Just to be clear, a transperineal prostate biopsy is when a medical professional removes multiple tissue samples from your prostate using a special needle inserted in the area between your rectum and your scrotum, aided by an ultrasound probe inserted in your back passage to visualize the process.

This is usually performed with a local anaesthetic rather than knocking you out (to reduce time taken, resources consumed, and risk exposure). Here's a diagram, taken from the video above:

|

| © 2021 Mechanisms in Medicine Inc. |

If you've googled "prostate biopsy" or watched the video above, you've probably noted that the transperineal prostate biopsy is a relatively new approach compared to the traditional method known as TRUS or transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy. As you can see from the diagram below, TRUS involves inserting both the ultrasound transducer and the sampling needle through the anus, then piercing the wall of the rectum to get the samples.

|

| © 2021 Mechanisms in Medicine Inc. |

The TRUS procedure carries greater risk of causing infection because it pokes holes in area used to store fecal matter. TRUS also has a narrower range of access to the prostate, as noted in the video at the top of this article. In other words, as a patient, if you have a choice, I'd say go transperineal: LATP rather than TRUS.

By the way, if all of this sounds pretty gross/scary/painful to you, be assured that you are not alone. Just the term "transperineal prostate biopsy" is enough to make a grown man squirm; each of the three words is discomfiting on its own, particularly if you are having problems with your prostate. And of course, the mother of all prostate problems is prostate cancer.

Typically, the goal of a prostate biopsy is to find out if you have prostate cancer. The tissue samples acquired by the biopsy procedure are analyzed by a pathologist who reports them to the urologist who requested the procedure. (I am writing this before receiving the results of my own biopsy because these have been delayed due to a shortage of pathologists.)

Legs up, lie back, and go to your happy place

When your biopsy is scheduled you will likely get specific guidance from the clinic-facility-urologist that is performing the procedure. General information on how to prepare for an LATP are provided in the pages to which I have linked below.

Two things you should discuss with the doctor before the procedure are a) the possible side effects, and b) the handling of any anticoagulants—like aspirin, warfarin, apixaban, and so on—that you may be taking. (More on that later.)

One tip I can offer is to ask about eating and drinking before the biopsy. I was told this was okay. However, two of the guys I met on the morning of the procedure had decided to skip breakfast, apparently worried about bowel movements relative to having something inserted into their butt. One of these chaps got dizzy and faint during the procedure, possibly due to not eating breakfast, and the fact that it was past 11AM when he went in. I went in about noon, having eaten breakfast at 7:30. I felt fine but was very happy to sample the biscuit selection as soon as I came out.

My biopsy was performed at a hospital but as an outpatient procedure, in other words, no overnight stay. After checking in and having my vitals checked, I changed into a hospital gown and my slippers (the hospital has a "bring your own slippers" policy). Then I sat in the staging area with several other blokes awaiting the same procedure. This led to some interesting conversations, like comparing PSA scores, sharing feelings of trepidation about the procedure, and generally asurring each other everything would be fine.

When it was my turn, a nurse walked me into the procedure room where I was directed to sit on the special table, with my butt right on the edge. I then laid back and the nurses helped me put my legs in stirrups to hold them up and apart.

This arrangement is likely more familiar to women than men, but the words "undignified" and "vulnerable" probably come to mind for anyone who finds themself in this position in a room full of strangers (okay, the room wasn't full but there were four or five people there besides me—thankfully all of them were friendly, sympathetic, and reassuring).

As soon as I was positioned correctly, I was asked to hoist my testicles and penis up and away from the perineal area. A nurse them taped them in place with a protective barrier. This is not particularly uncomfortable and is done for two very good reasons: keep your junk clear of the action,and avoid it getting hit with icing spray.

The icing spray was the next step, used to numb the perineal area ahead of the injection of a local anaesthetic. While the icing burns a bit, it does reduce the sting of the injection. Fortunately, you don't have much time to think about that because the doctor is now using a gloved and lubricated finger to probe your anus and insert the ultrasound device.

Which brings me to what, for many guys, is the big question: what's it like getting that thing pushed up your back passage? To me it felt like having a suppository inserted. It did not feel, to me, like a drainpipe, which is how one friend had described it.

Admittedly, I did some relaxation breathing before the thing went in and that probably helped, but remember, there is local anaesthetic and lubrication to reduce the discomfort. You really don't need to worry, even if your butt has never experienced a foreign object like a finger, suppository, butt plug, etc. (Tip: practicing with one or more of those things ahead of the procedure may help.)

To me, the more disconcerting sensation was the sample taking. This started as soon as the doctor was happy with his view on the ultrasound monitor. The sample "shots" really didn't hurt but neither did they feel good. I'd say they were uncomfortable, partly because the sound each one made was like a nail gun or heavy duty stapler.

I tried to count down the sounds while focusing on my breathing, knowing there were supposed to be 24 samples; however, that didn't distract my mind enough, so I switched to talking. (For me, talking can take my mind off other things—I've often thought that dental work would be less distressing if we could talk all the way through it.)

But what to talk about? I started by thanking everyone for being so cheerful despite having to work in masks and less than ideal conditions. Because this was happening in an NHS hospital in England I said that I thought everyone should get a big raise and large bonus. This was well-received, not least because I'm sure they could tell I meant it.

Eventually the "shooting" stopped. I had forgotten to set a timer but I reckon the sampling itself took no more than 15 minutes. I don't think there was a round of applause but the team seemed very pleased and gently helped me down from the table. (It turns out I was the last patient of the morning.)

I thought I heard the doctor say he had taken more than 24 samples but I might be mistaken as I was busy thanking everyone and adjusting my gown for the walk back to the waiting/recovery room. Walking and sitting down were not painful at that point and the nurse assistant brought me a coffee not longer after I sat down. And biscuits.

The final step before leaving is to make sure you can urinate. After sitting drinking coffee for a while I was able to pee just fine, and without any pain, but of course there was some blood. This is "normal" because your prostate has just had a bunch of holes punched in it and urine passes through a tunnel in the prostate to get from bladder to penis. However, I have to say that seeing blood in your pee is not normal and I found it took some effort to get used to this.

Because I was the last patient of the morning there were no other guys with whom to chat or compare notes. Earlier conversations had revealed a split between those who had a very negative reaction to the procedure ("I felt violated"), and those who found it reasonably tolerable. I was with the latter group. As it happens, I had experienced a wisdom tooth removal a few months ago and for me the biopsy was no worse than that. One bloke tried to make a joke about it being easier to deal with if you were gay, but I think he sensed the rest of us were not amused. I don't happen to be gay but I doubt that my response to the procedure would have been any different if I was.

Prostate biopsy: the aftermath

The nurse who discharged me made a point of telling me to take it easy for the next 10 days. She emphasized 10 and sort of winked when she said it, probably because that is quite a few more days than some of the recovery advice I'd seen on websites and in hospital literature (3-4 days).

In hindsight, I wish I had worked at taking it easier for longer, but frankly I felt pretty good almost right away. I drove myself home, and although sitting in some chairs felt a bit sore after the anesthetic wore off, there was no serious pain. There was blood in my urine, but no pain when peeing, and the amount of blood seemed to reduce over the next few days.

Something I found helpful during those early post-biopsy days was to wear a pair of incontinence underpants (Depend). These prevented blood stains on my regular underwear. The following table from Oxford University Hospitals shows what you may need to deal with after your procedure:

The first time I read this table I found myself discounting the odds, basically assuming that I was unlikely to be one of the "1 in X" men. And for the first seven days after the biopsy I only experienced first few items on the list, nothing else.What went wrong?

“New oral anticoagulation drugs (NOACs) are increasingly used. However, the management of such treatments is feared and not yet well known to urologists. A protocol for prostate biopsy management of NOACs seems mandatory.” (Coscarella et al., Ther Adv Urol, 2018, Vol. 10(12) 437–443.)

Notes

This is a good leaflet about LATP that includes the risk chart shown above:

https://www.ouh.nhs.uk/patient-guide/leaflets/files/59654Ptransperineal.pdf

Good web page with diagram of LATP

https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/prostate-cancer/getting-diagnosed/tests/transperineal-biopsy

More extensive discussion of transperineal versus transrectal prostate biopsy:

https://www.mayoclinic.org/medical-professionals/urology/news/ultrasound-guided-transperineal-prostate-biopsy/mac-20473283

Personal note: One reason I created a "personal blog" was to have a place where I could share information that might seem inappropriate or out-of-place on a professional blog, such as the "Cobbs on Security" site. That is why, in the archives of this site, you can find articles about my adrenalectomy and primary aldosteronism, a condition that can cause high blood pressure and heart damage. In fact, my long standing persistent atrial fibrillation was probably caused by late diagnosis and treatment of primary aldosteronism. That late diagnosis was partially attributable to doctors not doing enough talking to each other.

No comments:

Post a Comment